Research into clay provides clues as to how much water there was on Mars

Clayground explores clay wherever it occurs. There is abundant clay on Mars. Clay Geochemistry Researcher, Javier Cuadros, describes detailed research comparing minerals on Earth with those on Mars. He has written this article for us about his investigations into the question:

How wet was Mars? Clues are found from research into kaolin clay.

Kaolin is a familiar type of clay. Over the centuries, kaolin has been used to create delicate ceramic wares. China clay is mainly composed of kaolin. From the scientific point of view, kaolin comprises a group of three very similar minerals, of which the most common by far is kaolinite.

Deposits of kaolinite are generated by enormous amounts of water passing through silicate rocks (all rocks have pores and fractures) or soils which end up dissolving and carrying away most of the elements in the rocks. The water may be hot as a consequence of volcanic processes, where the heat keeps it circulating vigorously, or may arise from the abundant and frequent rain of equatorial climates. In both cases, generation of large amounts of kaolinite takes hundreds of thousands of years or more. Acid waters are effective generators of kaolinite because they attack the rock very vigorously and accelerate kaolinite formation. The source of acidity however is rarely sufficient to produce large kaolinite deposits.

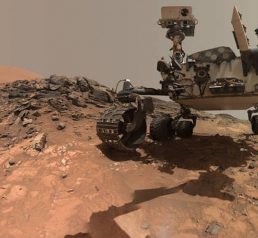

The discovery of kaolinite on Mars with remote sensing from man-made satellites caused great excitement. The existence of other types of clay on Mars had indicated that there was “abundant” water on the planet at the early stages (more than 3 billion years ago). Just how abundant is still a matter of debate. The point is that kaolinite formation requires a lot more water than other clays, and kaolinite on Mars seems to indicate that water was, at some stage, fairly abundant on the planet.

Or was it? Scientists had to look closer into the question. Approximately just 7% of clay detections on Mars are kaolinite. In other words, kaolinite-forming processes took place rarely and in a thinly dispersed manner. This argues against the “fairly abundant water” hypothesis. The main tool for mineral-mapping with remote sensing on Mars is infrared sprectroscopy. In these studies minerals produce characteristic peaks that indicate their presence in the rocks. , It is known that kaolinite is a rather loud mineral in infrared investigations and overwhelms the signal from other minerals.

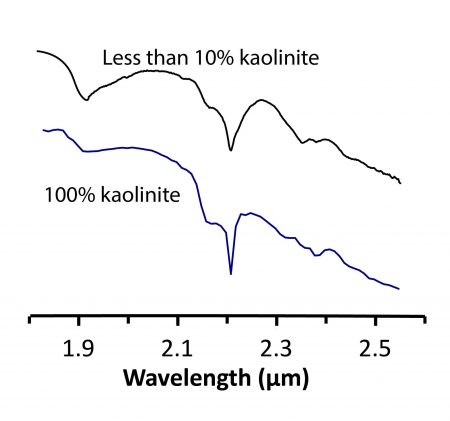

To see how loud, look at the figure below.

The figure shows a section of infrared spectra of (top) a rock containing less than 10% kaolinite, with other clays and minerals, and (bottom) pure kaolinite. The downward peaks indicate what minerals are present in the mixture. One can see that the spectrum with 10% kaolinite is almost identical to the one with pure kaolinite, which means that the peaks from kaolinite entirely dominate the spectrum where there is only 10% kaolinite.

The spectra were taken in a laboratory on Earth. These are the type of data scientists use to recognize minerals on Mars: the patterns of the lines tell about the minerals on the surface of the planet, as they do about the minerals in a sample in the laboratory. Kaolinite is so loud that a few percent of it generates an infrared spectrum that looks like pure kaolinite. This leaves us in doubt as to how much kaolinite is present in Martian rocks where we detect it. In consequence, there is no way of assessing how much water was needed to make it: much kaolinite requires a lot of water, little kaolinite requires less water.

These are lessons learned from investigating Earth analogues: places on Earth that resemble specific locations on Mars. Javier and colleagues investigated rocks with kaolinite in the Riotinto area in South-East Spain. The peculiarity there is that kaolinite was generated by acidic waters, as is suggested in more than one location on Mars. Javier and colleagues found rock that had been only partially transformed into kaolinite, but where the infrared signature of kaolinite became dominant from low kaolinite content. Because acidic waters are aggressive and accelerate the kaolinite formation process, the kaolinite in Riotinto could have formed with little water.

Rocks from the Riotinto area (South-East Spain). There is kaolinite within the whitish patches.

So, after all, kaolinite findings on Mars do not necessarily indicate the action of large amounts of water. If there is little kaolinite in Martian rocks, the amount of water required was less. If the water was acidic, as implied in some Martian locations, still less water was required. In fact, other indicators found on Mars point in the direction of water scarcity. At this stage scientists tend to think that water was not abundant enough to produce drastic changes in large volumes of rock. If Mars is ever colonized, kaolin mining is not expected to be a profitable activity.

On Earth, the large volume of water and the long period of water-rock interaction has generated wide mineral diversity of innumerable “flavours”, one could say. On Mars, most of the planetary surface, even if modified by water, retains the “flavour” of the rocks formed when the planet solidified or by later volcanic activity.

-

Pandemic clay action!

18th Aug 21

-

The Volcano and the Microbes: interaction between geology and biology

4th Jun 21

-

Perseverance: a new NASA rover continues to follow Martian clay

2nd Aug 20

-

Research into clay provides clues as to how much water there was on Mars

18th Sep 19

-

22 Hands: British Ceramics Biennial Commission

12th Aug 19

-

Clayground Summer Events

24th Jun 19

-

Colourful Clays on Mars

20th Feb 19

Thames foreshore fragments and visual references

4th Dec 12

How is clay formed? Is it inorganic or organic?

10th Sep 12

Clay Cargo 2014 Collection: the Thames Foreshore

15th Dec 14

CLAY FROM AROUND THE WORLD

3rd Aug 11

Clues to life on Mars likely to be found in clays, Javier Cuadros

5th Aug 16

Clay Cargo 2013-2015

15th Jun 15

Sessions on the Clay Cargo boat, hosted by Fordham Gallery

9th Mar 15

Civic Spaces, Exhibitions

Museums and Galleries, Regeneration

Maker spaces, Rural Sites

Archaeology

Youth and Adult Community Groups, Professionals

Art Groups, Families, Students

Collaborations, Archaeology Sheets

Commissions, Thinking Hands? Research

Knowledge Exchange